Hello lovely readers! I live in an old brick bungalow in Salt Lake City, UT, with my handsome ride-or-die husband and anxious rescue dog. My husband has three grown kids, and we recently fostered a boy from Ukraine. I’m working on finishing a PhD in English Literature this year, and am itching for a regular 9-5 job outside of academia! I grew up in Sweden, and that’s where most of my family still live, but spent years in Sudan, Africa, as a teenager and went to college in England, and eventually ended up in the US of A for graduate school. I’m so honored to participate in this interview, and share some of my perspectives on disability. If you are not sick of me after these rather wordy responses, you can find me on instagram @lisamarietheswede.

Miggy: Hi Lisa! Thank you so much for being here today. As much as I love hearing from families and their journey in becoming a special needs family, I also love hearing from individuals with disabilities who can talk about being an individual with a disability. Can you take me back to the beginning? Were you born with a disability or was it something that happened a little later?

Lisa: I was born with spina bifida– a fancy Latin term for a disability that basically means my backbone didn’t close completely over my spinal cord in the womb, and everything below that ruptured point on my spine was consequently affected and a little bit weakened. My disability was a surprise to my parents and, therefore, I think quite terrifying news initially, as they didn’t know what the diagnosis would mean for my life or for theirs.

Back in the 80’s, when I was born, there was only really one ultrasound during the pregnancy, and my adventurous mother was blissfully round and happily gallivanting in Turkey for that scheduled appointment and completely missed it! In addition, my parents’ had my older sister, their first born, two years earlier, while working and living in rural Rwanda, and her dramatic delivery involved an announcement on the local radio that the “white woman” was going into labor and my father crossing a national border at breakneck speed on a motorbike in order make it in time and a lizard slowly scaling the wall of the primitive hospital room where my mother pushed and pushed. So when it was my turn, and my parents were back in Sweden, with all the latest medical advancements and a reliable socialist healthcare system available to them, they did not anticipate any complications. But there I was, not what anyone was expecting, demanding that they adjust their lifestyle, living arrangements and understanding of what counts as a “healthy baby.” My father always tells the story of how I came out and the doctor’s face changed and suddenly the room was full of white coats and tense debate and hushed speculation. He had to sit down. Exams and surgeries followed, and a long hospital stay, and, eventually, an encouraging verdict from a sensible medical expert that I wouldn’t exactly grow up to be a ballerina but that there was no reason I couldn’t do everything I set out to do, at which my dad sighed with relief, having never cared for the ballet.

My sense, based on my subjective reconstruction of the past and my parents’ memories that I internalized as my own origin story, is that there were a lot of “what ifs” and questions and uncertainties but that I was unequivocally loved from the beginning and excitedly welcomed.

.jpeg)

That said, I know one of my mother’s most vivid memories attached to my tumultuous arrival is a nurse in the hallway expressing that it was a shame a proper prenatal screening had not been performed, because then my mother would have known beforehand, and could have “gotten rid of it.” It broke my mother’s heart that the same birth that filled her with maternal pride and joy, now the mother of two babies (twice as many babies as the day before!), inspired pity in a bystander. I mention this passing remark fully aware that the recent American CBS report on Iceland’s DS rates has sparked heated responses and a renewed media interest in selective abortion, but I want to emphasize that denying the quality of life or worth of people with disabilities (physical or intellectual) is nothing new, and many northern European countries have similar statistics and have had them for a long time. And, in a larger sense, beyond the prenatal technologies we rely on today, there is of course a long brutal global history of systematically removing, sterilizing and institutionalizing individuals with disabilities. I think of that nurse’s offhand comment as also illustrating how ableism [the prejudice and social discrimination of people with disabilities], in all its structural and varied manifestations, is brought to bear on even the earliest moments of a disabled life.

Because abortion is such a hot-button partisan issue in the U.S., many activists normally committed to an intersectional feminism that includes disability justice seem to have fallen silent. The conversation has largely been hijacked by a particular group of white-haired pro-lifers wielding divisive and shaming rhetoric that shuts down healthy debate and excludes contrary positions rather than invite diverse voices to the table. I am eager for this conversation about bioethics and disability and the supposed “prevention of suffering” to be afforded the same space and serious attention as other important conversations about the rights of other minorities, and for that conversation to be spearheaded by people actually in the disability community since they are the ones whose lives and bodies are being verbally bandied about. All this to say that, throughout my conscious life, as I was growing up and into my particular body, I carried the sense that my existence, and the way I live in this world, is political in and of itself, and always has been. I think in a way those of us with a body deemed a-typical or dis-abled or ab-normal offer the world a gift by simply continuing to go on furiously living, by unapologetically insisting on our manner of being alive and the contradictions and possibilities inhabiting our corporeality.

.jpeg)

Miggy: I’d love to hear about your family life growing up. Were your parents supportive and if so, in what ways did they encourage and support you? Do you have siblings? If so how was your relationship to them growing up? Is there something your parents did really, really well for you as a child? Is there anything you wish they would have done differently? At what age did you realize you were different from your siblings or peers and how did you come to terms with that?

Lisa: I would say that my childhood was very happy and ordinary and mostly void of defining moments where I felt separate or strange, and that my place in our family and immediate neighborhood community felt obvious and natural. I spent my younger years petting and feeding my bunny, endlessly cleaning and rearranging the furniture in our small playhouse in the yard with my two sisters, attending Girl Scout activities and thrilled to learn how to write cursive in third grade. In the way of most young children, I think, regardless of ability, I was very proud of my body and mesmerized by what it could do. I had a little red walker when I first learned how to stand, and then transitioned into leg braces to walk independently, but also used a power chair for longer outdoor distances, as well as a manual wheelchair. I think that range of mobility (I also did a fair share of biking, horseback riding and swimming), and the way I learned to compensate for certain limitations with creative alternative maneuvers brought me a lot of joy, and impressed my friends, at least when we were younger. Even now, my sweet open-minded 6-year-old niece finds my movement, and my easy swapping between the wheelchair and walking, to be fascinating, fun and convenient.

And my parents really nurtured a family culture where they recognized each of our strengths, as three individual but connected sisters, and always told us that the world needed those specific strengths, but without ignoring our very real weaknesses and limitations. When bragging about us, or introducing us, they would often say things like “Hanna is very social and has never met a stranger, Lisa has a sharp mind and a quick wit, and Kristin is inventive and has tons of original ideas!” My sisters and I are very close but have always been very different, in terms of personalities and interests and life goals, so, in many ways, my disability was just another one of those differences, and my parents treated it as such. My parents were also committed to travel and service and we lived in Sudan, Africa, for most of my teenage years. There the color of my skin and the consequent perception of our family as affluent and Western trumped any other identity categories. My wheelchair was just another odd thing those weird white people used! In short, my parents did a lot of things that other folks thought were mildly crazy, and so my disability was not on the forefront of my mind as particularly odd, as I took in the world and decided who I wanted to be.

But that delight in discovering my body’s abilities and quirks changed as I returned to Sweden for High School and experienced culture shocks and looked pale and pimply in the mirror and grew to detest the dark climate and fashion obsessed youth culture. It’s so cliché, I know, but realizing I was a woman and not a child, or young girl, anymore was disorienting, and I didn’t fit or belong in the same way. Suddenly I wasn’t so interested in forging my own unwieldy path but wanted a map to follow, and there was none. I can honestly count on one hand the number of films and books I encountered in high school/college that had some kind of representation of disability (and they were usually unflattering portraits of disabled people, always attached to tragedy or upbeat unrealistic heroism). It wasn’t even that I felt excluded from a lot of settings or common adolescent milestones—more like I couldn’t even imagine what it would look like for someone like me to be included, in dating a boy or spontaneous trips to the city with my girlfriends to shop—there was no imaginative space for that to play out, for me or my peers.

Suddenly I became more visible in public and strangers were not so impressed with my shape shifting self. Many adults were outright offended when I was out and about and got out of my wheelchair to walk, as if I had betrayed or tricked them. I have been angrily asked too many times to count why on earth I own a wheelchair if I can walk and evidently don’t need it! I learned that people like either/or and I was both/and, that people like neat water-tight identity categories and I upset that equation. They would see me wheeling and feel instantly sorry for me and then see me get up and walk with my braces and have to reassess, trying desperately and unsuccessfully to fit my body into the narrow stringent narratives of disability they’d acquired. I even had friends with spina bifida who surrendered all their walking and used their wheelchairs fulltime, even if they had some upright ability, because it was too exhausting to live in two worlds and constantly field those types of questions. I found that public response to my body so depressing and odd. Why wouldn’t we celebrate multiplicity and alternative modes of movement?! (See Aimee Mullins’ beautiful TED Talk. Mullins presents the possibility of an open and curious relationship to our bodies, and suggests that prosthetics/adaptive devices can endow disabled people with potential that able-bodied people do not yet possess!)

So, I struggled to experience life as a whole multi-faceted being, as a complete spiritual, sexual, contradictory, vibrant, muted, selfish, open-hearted, lazy, ambitious person. I felt particularly uncomfortable in the area of sexuality and dating and partnership. I would have drunk men yell at me wheeling down the street things like “you’re really pretty for being in a wheelchair!”, notably uninterested in expanding or transforming their ableist view of disability and instead attempting to assure me that I could “pass” as an able-bodied person. Eventually I was pursued by a number of men who were not creeps and drawn to me because of who I was, not despite or because of my disability, and ultimately met the man I’m now married to! Marriage is wonderful and being “one flesh” with my partner has been so liberating and empowering. There is nothing figurative about being “one flesh” for us—beyond the sexual implications, of course, my partner and I borrow and balance out and rely on each other’s bodies every day. I love our joint creative acrobatics! He has enabled me to be much more bold in my bodily expressions (just one small but significant example would be that I am now okay showing off my legs/braces and wear the shortest skirts and shorts in all the land!) and daily counters the damaging and established paradigm of the disabled individual as a “burden,” instead of an asset, to his or her community.

.jpeg)

Miggy: Having a daughter with a power chair we have quickly learned that the world is not accessible! As a disabled adult what is your day-to-day like? Is accessibility a struggle in your daily life? In short, what do you want able-bodied people like myself to understand about the importance of accessibility?

Lisa: Yes, the world is definitely inaccessible! Or, rather, it’s accessible to certain types of bodies, and architectural spaces are designed to accommodate particular, normative people. As a wheelchair user, I’ve been forced to learn to constantly pay attention to my surroundings and landscape, and plan accordingly. It’s exhausting, and makes this fiercely independent gal quite dependent on others, and I often find myself jealous of my able-bodied friends who seem to have such an unthinking and casual relationship to time and space. Sometimes I daydream about being wasteful with time and not having to think ahead or calculate beforehand or plan meticulously how I will access certain buildings with stairs or new unfamiliar locations. It’s not all about man-made spaces, though—I can find myself grieving my inability to access stunning mountain tops or a maddeningly sandy beach, profoundly missing something I’ve never fully known. I’m not a particularly sporty person, but I do love the outdoors and nature and occasionally I get mad that I hear the call of the wild so loud and clear but my body feels ill-built to respond to it! I started sit-skiing, at the age of 30, and experiencing previously inaccessible terrain becoming the vehicle for speed and adrenaline was truly exhilarating and made me cry.

But I think one tangible way to think about accessibility, as a whole, is to consider the uneven power dynamics embedded in access. It’s not just that I am prevented from entering, or unwelcome in, certain spaces, it’s also that able-bodied people often feel that they are entitled to undue access to me. Access is a two-way street. All those unspoken social rules pertaining to how you relate to friends, acquaintances, strangers, and the rippling circles of sociability beyond that, break down when you have visible disability. It is rare for me to leave the house and not receive some kind of comment or stare from someone I don’t know, as I walk (wheel) my dog, as I go grocery shopping, etc. There is something about a wheelchair that signals to people that they can approach me, speak to me, ask personal questions about me, watch me, even touch me. The only thing I know to compare it to in the able-bodied realm of experience is a pregnancy, and a random stranger suddenly feeling confident to rub a woman’s belly on the bus, except a wheelchair has none of the fuzzy, warm, miracle-of-life associations! People expect me to educate them, to answer their probing questions, to explain myself to them, surprised that I might feel violated or infringed upon within that exchange. Often passersby won’t even begin a conversation with a preface or an introduction but will just blurt out something like “what happened to you?” or “do you like being ‘in there’ (meaning the wheelchair)?”, and they are shocked when I don’t immediately catch on or know what they are referring to, because, unlike them, I am not moving around perpetually preoccupied with the thought that I’m moving around using a wheelchair.

I think if we want to create truly accessible spaces, ramps are important but so are the mechanics of relating and the visible and invisible barriers that prevent a connection as equals. We need to be conscious and critical of who feels empowered and who feels disempowered to know and be known by others, and how that (in)accessibility is reflected in physical and material structures. A small but meaningful example of that consciousness would be to make your home accessible, right in the doorway! My husband and I make a point to tell anyone who enters our house that they are free to keep their shoes on or take them off or borrow slippers. We keep our house accessible and welcoming in this way because I am unable to walk or use my braces without shoes, and I have been a guest in so many homes where the moment I’ve crossed the threshold the host has requested all shoes be removed, to keep the floors clean, and I’ve been mortified that I cannot comply. Now, that’s a purely practical detail but it plays a huge role in how welcome you really feel in someone’s private home and often sets the tone for the rest of the evening and partly determines your ability to connect within that space. So, start small, with you own spaces, that you have influence over, and ask yourself in what ways you might be living an inaccessible life to others?

Miggy: Now for a lighter question, I’m a big believer in seeing the humor in life and learning to laugh, so have you ever had any funny conversations/moments you never imagined due to your special needs situations?

Lisa: Oh, there are so many to choose from, ha! But one of my favorite hilarious crip moments happened in Israel when I was about twelve years old. During one eventful season of our upbringing, my parents took each one of us kids on a longer trip, for a special adventure and solid one-on-one time. I got to travel with my parents to see Jordan and Israel, and we had an amazing time riding camels in Petra, floating in the Dead Sea and, most significantly for this story, tracing the path Christ, bloodied and broken, is meant to have carried the cross to his crucifixion. It’s a winding street in the Old City of Jerusalem, called Via Dolorosa, or the “Way of Suffering”. It’s more narrow than you would think and flanked by houses on both sides. I don’t know if they were inserted later but at present the steep dirt road has low wide steps leading all the way up, like a gentle staircase. It was much too far for me to walk the whole way so I took my manual wheelchair, and I was also in a particularly persistent phase where I wanted to do everything by myself, with no assistance, and absolutely no parental pushing. So there we were, the three northern Europeans, moving slowly through hoards of tourists, in this religiously reverent and historically weighty place, me working up a sweat in the sun, bumping up that dusty incline, and refusing to let my parents help. I don’t think my parents have ever received so many judgmental and disbelieving glances in all their years of parenting me—packs of camera-carrying tourists, stopped, dismayed and embarrassed, half wondering if I was performing some kind of Christian ritual in imitation of Christ’s suffering! I smile thinking about that slightly diabolical and fiercely stubborn twelve-year-old pilgrim! I like her. Joking aside, as a person of faith, I do like to think there is also something true and poignant and revealing about that moment, that memory. Perhaps it exposes an ironic discomfort with disability in a faith community that boasts a main character who was bruised and battered, but definitively conquered that pain and that death, but then chose to rise from the grave with wounds still intact on his hands… But that’s another conversation, for another time!

.jpeg)

Miggy: I’ve written a few posts about the problem with pity (here and here) when it comes to having a disabled daughter and how her biggest obstacles aren’t her physical limitations, but the limitations that come from society and from people who think of her as “a poor thing” or who “feel bad for her.” I’m curious if you agree that accessibility and physical limitations are smaller problems than pity and the way the public sometimes views the disabled community.

Lisa: Yes, I definitely agree with that. I generally subscribe to what’s usually referred to as the “social model of disability,” which broadly argues that although there are real physical limitations and impairments facing individuals with disabilities, there is a social and systematic discrimination against people with disabilities that is self-perpetuating and often detached from those physical realities. I can honestly say that I have encountered those discriminating narratives and attitudes about disability everywhere I have lived in the world. Although, the narratives do vary somewhat, depending on the cultural context. In Sweden, my country of origin, for instance, people often ask me questions like “what do you have?’ or “what’s wrong with you?” and they are looking for an answer anchored by a medical term. Swedes feel most placated, I’ve found, when they can categorize me satisfyingly in relation to a scientific body of knowledge! In the US, on the other hand, people mostly ask “what happened to you?” presuming a “before” and an “after” and usually a tragic incident that brought me from that sunshiney “before” into the dark “after,” and a constant laboring to return to that innocent “before” stage. Of course, this has been my body for always, and my life is not tragic, and phrasing questions in that way partly determines my possible answers, which makes it difficult to respond truthfully and with dignity.

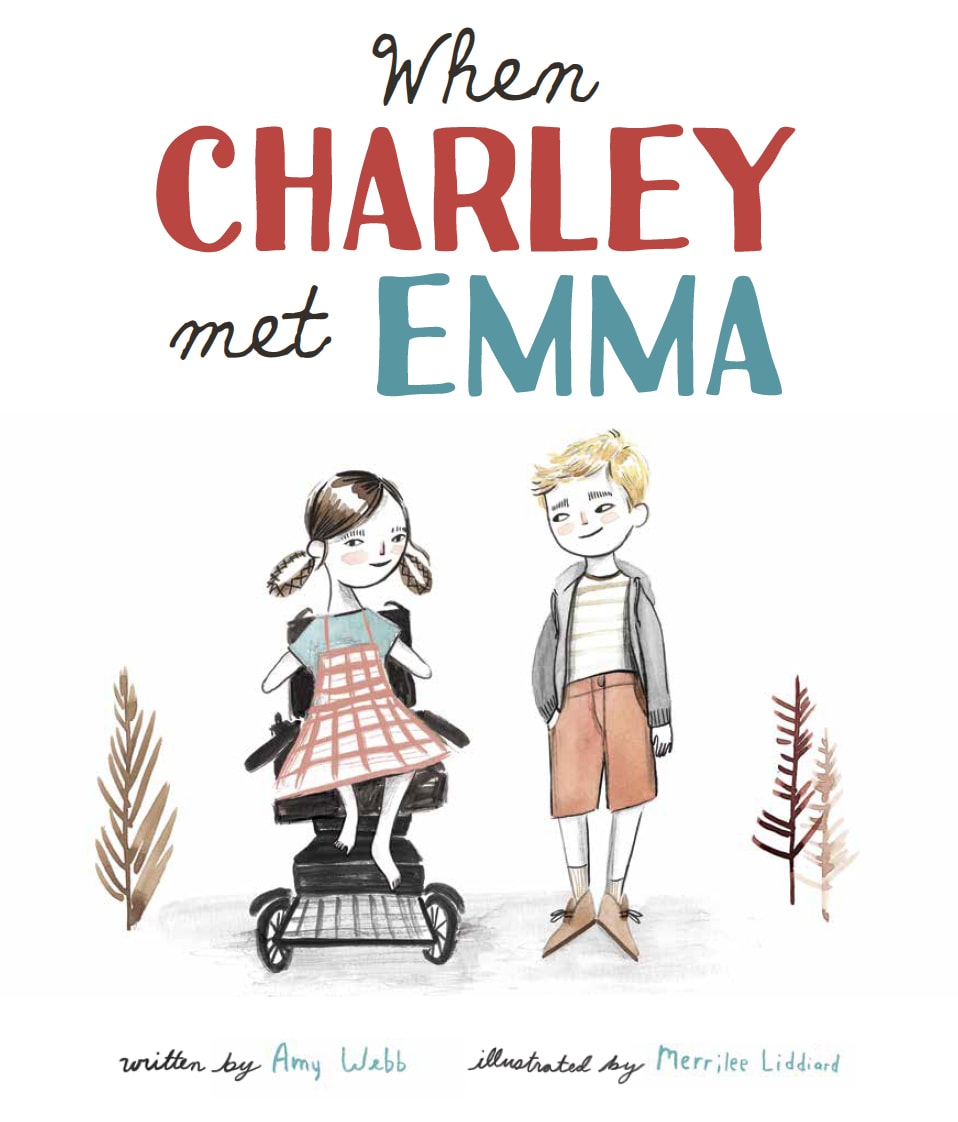

I suspect that kind of question has something to do with the prevalent stories in America trickling out of sports and the military. Teaching American undergrads, I have found that, overwhelmingly, the stories of disability that students are familiar with are framed within the predictable formula of an extremely athletic body damaged by an accident or violence, and they proudly bring in sensationalist media coverage of quarterbacks and vets who, despite all odds, through sheer force of will and determination, “overcame” their disabilities. By all means, everyone needs to do their thing (You do you, Lance Armstrong! (Except the doping, of course…)), but for those of us not living according to the ideologies of that script, we need to tell and share other, diverse, alternative stories of disability. And we’d also like to sometimes consume other, diverse, alternative stories of disability! As my husband frequently complains, “Sometimes I would just like to watch one movie that features a normal character who happens to use a wheelchair who just works at a f***ing bank!” Amen.

In general, I do believe there is a danger in any one single narrative of disability displacing all other narratives. As helpful as the social model of disability was for me, in my twenties, I recognize that on a global scale, that model is a luxury few can afford, or woefully irrelevant. In Sudan, the opportunities for kids with disabilities are very limited, and often disability is synonymous with a life as a social outcast, surviving on begging, unable to access meaningful work. I was fortunate to be born in Sweden, where health care services and adaptive equipment and accessibility modifications did not require a fundraiser or a charity event in church but were my right as a citizen. That privilege is not lost on me, and I feel nauseous with the wealth of it. As we work towards a more inclusive and fair and kind world, let’s not use the West as our constant frame of reference, but consider a disability justice that holds up morally trans-nationally.

Miggy: Living with a visible disability has unique challenges, in an ideal world how would you like people to approach and/or respond to you? Is there something you wish other people knew so as to avoid awkward or hurtful situations?

Lisa: An aspect of your instagram account and blog that I really appreciate is your attention to how disability is often cast as absolute difference, or the antithesis to an able-bodied life. I know many men who are proud to call themselves feminists but would never contemplate acting as an ally to the disability community. There is a deep-rooted fear of association there, which is peculiar, since, after all, you are substantially more likely to become disabled tomorrow than you are to suddenly decide to change your gender. Perhaps it is precisely that possibility, that gut sense that everyone, unless you die very quickly, is merely temporarily able-bodied, which renders the able-bodied majority reluctant to advocate for disability rights. I don’t know. But I think your posts on how parents can teach their kids to approach Lamp are extremely important, and full of useful tips, and insights to maintaining your sanity amidst the life-long deluge of hurtful and awkward situations. I think if people could suspend that initial normalized reaction to disabled individuals for half a heartbeat, of wanting to ask or help or look, that would go a long way. I am always so grateful when strangers make an effort to truly see me, and what I’m capable of, rather than tap into how they think they should feel towards me. So many good, life-giving connections and conversations are waiting to be had, but they won’t happen if people are too nervous to depart from the script!

.jpeg)

Miggy: Lastly, if you could give any advice to a mother whose child has just become disabled what would that advice be?

Lisa: I would advice a new mother to a disabled child to be ballsy and brave, to keep her eyes level and steady, without all that glancing to the left and the right, and intentionally define what constitutes “normal” for her family. Don’t worry so much about what other kids do or whether your kid will do those same things, but let your amazing child take the lead in making an original unbridled life! I think the world is hungry and hopeful for families like those. As a step/foster mama in a blended family, I am preaching to myself here, and I’m sure I’m not saying anything that hasn’t been said before, but in my experience, comparison is unproductive and reeks of fear. It prevents us from evolving into something new, or offering our surroundings the most stunning, idiosyncratic and human version of ourselves. Let go–life is always a gamble, you never know what kind of body or baby or beauty you are going to get–those things were never ours to control anyway.

Love,

Lisa

This was an amazing spotlight. It was clear to me by line three that Lisa is WAY BETTER at expressing herself with the written word than I will ever be 🙂 Thank you, as always for opening my eyes on Friday morning.

This was a very good read. I intend to be inclusive and I hope my own timid mess and confidence issues don't get in the way! I hope my children learn to be friends and advocates with people no matter what their different abilities and talents are. ?

I must second what Allison noted: Lisa is an excellent writer and insightful, smart, ballsy thinker. Thanks, Lisa, for sharing your experiences and perspective.

I really, really appreciate this spotlight and the insights Lisa offers. Thank you!