.jpg) Hello! I originally wrote this post back in 2019, and I decided I needed an update. Most of this is in it’s original form, with some updates and changes that reflect my ever growing understanding of disability, inclusion and education.

Hello! I originally wrote this post back in 2019, and I decided I needed an update. Most of this is in it’s original form, with some updates and changes that reflect my ever growing understanding of disability, inclusion and education.

For years I have shared an updated version of this post, as it seems like every year I gain new insights and understanding. In the past I’ve written two versions of this post–one is how to navigate a special needs encounter, which is to help parents and caregivers know what to do when a non-disabled child meets a disabled child, for this first time. The write up I did at Cup of Jo is my favorite version of that post–you can read it here.

The other version of this post is How to Talk to your Kids about Disability, which covers a lot of the same material, but the main difference is you’re being pro-active and talking to your kids about disability ahead of time, rather than waiting for an uncomfortable situation to arise.

This year I’d like to take it a step further with my thoughts on How to Raise Disability Inclusive Kids.

Like other identities, disability is not something you can just ignore and hope your kids will “get it.” And like other identities–race, gender, sexuality–people with disabilities aren’t embarrassed or ashamed to be disabled. It’s not the whole of who they are, but it is an important part of who they are. Keep in mind, that if you were to talk to your kids about race or sexuality, would you say it in a sad tone that conveys you feel bad for people of color for being people of color? Or that you feel bad for gay people for being gay? No! Of course not. Too often people think of disability as inherently sad, negative or undesirable, but it’s not and therefore it’s important that when you talk to your kids about disability it’s not a “isn’t this so sad?” kind of discussion. Disability is full of color and variance and is just another way to exist in this world. Without further ado, these are my tips for raising your kids to be inclusive of their disabled peers.

.jpg)

1. Bring disability representation into your home.

This is key. This used to be my second tip, but I’m going to explain below why now it’s my #1 tip.

Bringing disability representation into your home looks like buying or checking out children’s books that feature disabled characters, include TV shows with disabled characters in your kids screen consumption and you can even make a point of shopping at stores that are inclusive in their advertising.

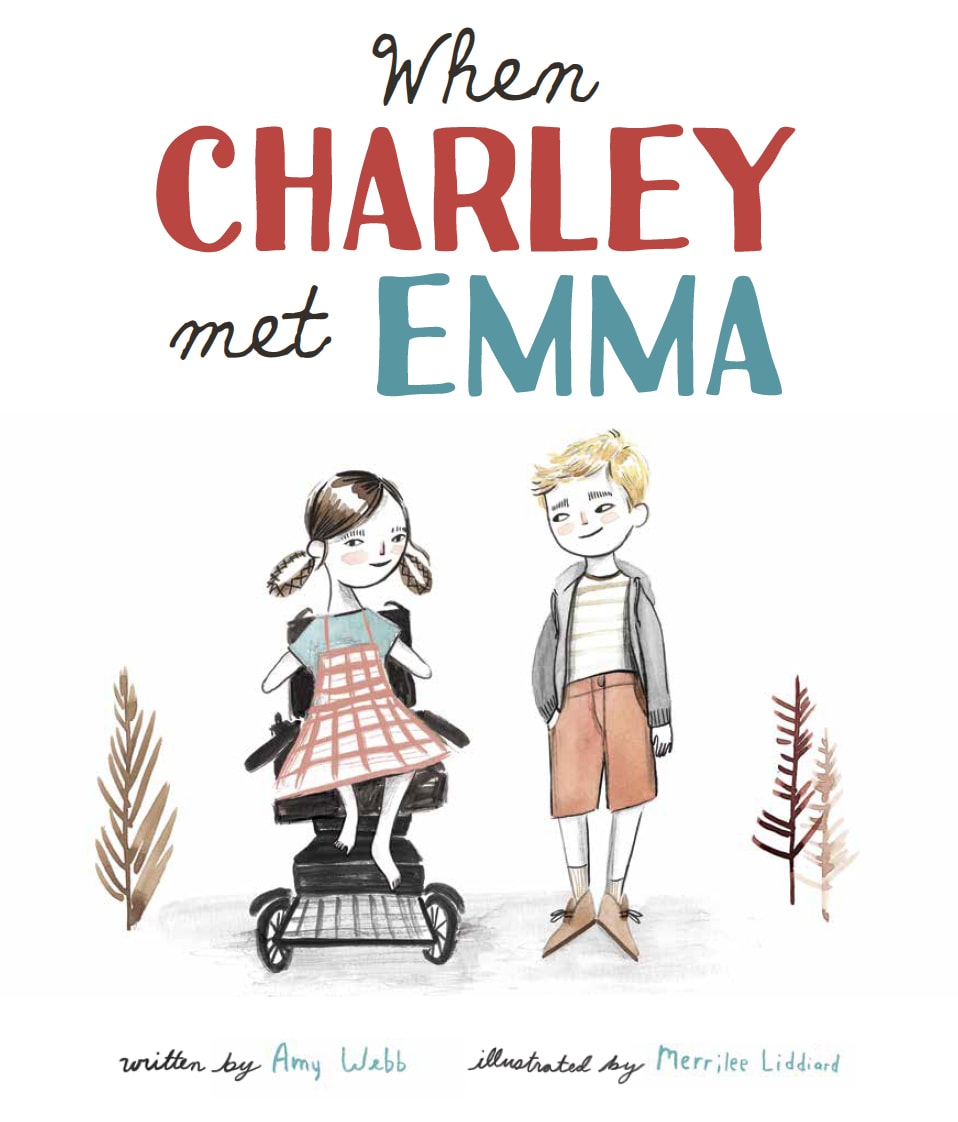

In addition to my books, When Charley Met Emma and Awesomely Emma, there are a lot of great options out there–you can check out this post for my top disability based book recommendations with books like Hiya Moriah, All the Way to the Top and I Am Not a Label and one that is not on my list because it just came out this year, What Happened to You? For older kids they might enjoy Born Just Right or Insignificant Events in the Life of a Cactus (which I have yet to read, but Lamp likes it) El Deafo and Out of My Mind.

I wrote When Charley Met Emma and Awesomely Emma with the hopes that one day my daughter can go to college, get a job, support herself, find accessible housing, get married and have kids (if she so chooses). How does writing a children’s book featuring a child with disabilities help Lamp got to college, get a job and get married?

Because REPRESENTATION MATTERS.

If that seems like a huge leap to say that having more representation in media will equate to my daughter getting a good job, well… it’s not. If people don’t see you as a part of the world around them, do they see you at all? Are you viewed as a valuable member of society who has much to contribute? According to this article from Huffington Post, no. “There’s this body of research and a term known as ‘symbolic annihilation,’ which is the idea that if you don’t see people like you in the media you consume you must somehow be unimportant. (In a 1976 paper titled “Living with Television,” researchers George Gerbner and Larry Gross coined the term with a chilling line: “Representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation.”)

And a new study out of the UK confirmed that “confirmed closing the gap in disability representation in kids’ TV shows can lead to more disability inclusion and understanding in the real world.” This is one of those things that seems obvious to me, but in this day and age I guess it’s always good to have a study confirm these things.

Also, let me share this DM I got from a mama who had bought my book and read it with her kiddo. “I was at the park this morning with my kiddos, and there was a little bot there with a limb difference. My boys said, “Hey! What’s your name? I noties you have a limb difference. That’s super cool.” The mom told me she has never (being a mom to a kid for 5 years with a limb difference) had a child say “limb difference” or tell him it was cool. Mostly kids say it’s creepy. I told her about your book and recommended she sent it with him on the first day of kindergarten in August. It was the SWEETEST.”

When children have even a little bit of knowledge and a small point of reference for disability it can make such a BIG difference.

.jpg)

2) Talk to your kids about Disability.

The reason I have “bring disability representation into your home” as the #1 suggestion, is that it’s A LOT easier to talk to your kids about disability when you have a refernce point to start with. I get notes from parents all the time telling me what a great conversation starter my books are–which is exactly the point!

Also, if you have any sort of back-to-school talk you give your children or if you regularly bring up important conversational topics around the dinner table (as we do) you can bring up disability during these times as well. For really young kids, a great way to start this discussion is to talk about common differences like eye color, hair color and of course skin color and to point out that everyone is born just a little differently. Then you can bring in some slightly bigger differences like asking if they know of anyone who wears glasses (maybe they wear glasses!), or maybe you have a family member who uses a walker or a cane or if they know any kids at school who use a wheelchair, or need extra help.

Then you just call it what it is–a disability. According to the legal definiton as definited by the Americans with Disabilities Act (the ADA) a person with a disability is someone who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity. For kids I say, it’s when your body or your mind works differently from how most other people’s bodies and minds work. Having a disability isn’t bad, sad, wrong or strange, it’s just different. We often say, “Lamp was just born this way” and “This is how God made her.” I also think it’s a great idea to show them pictures of individuals who might look a little different than they look and teach talk about some of these differences. You can show them Lamp who has limb differences, Catherine who has muscular dystrophy, Lily who has Down syndrome, Zayn who has dwarfism, Brenna who has Harlequin Ichthyosis, Noah who has trisomy 8 and cerebral palsy, Elizabeth who has one leg, Sarah who has Apert syndrome, cute little Ruby and many, many more.

This is also a great time to explain that some differences we can see on the outside, but some differences are on the inside and we can’t see them. Like Cole who has epilepsy, Luke who is autistic, or Wyatt who has severe food allergies and again, many, many more. I also love the 2016 Paralympics Promo Video and this one from 2012. I think it’s really great to show kids all the things a different body can do.

It’s also important that we don’t play into the victim/hero stereotype of disability and insist that a disabled person has to “overcome” their disability. People with disabilities are also just regular people and accomplish a lot of things that regular people do. You could show your kids that children with Down syndrome go to college too, teach preschool, and that people without arms have regular jobs like Richie Parker of NASCAR or Jessica Cox who is a pilot. The point is we all have strengths and weaknesses, and people with disabilities are no different.

In your discussion remember the key points from my other post:

1. Questions are OK.

2. Be kind

3. Find common ground.

4. People with disabilities are still able and have things they’re good at.

.png) 3) Encourage genuine friendships.

3) Encourage genuine friendships.

Building an actual friendship is much more than just waving hi and “helping” a child with a disability at recess or even sitting by them at lunch occasionally. And it is certainly more than inviting a disabled peer to prom–inviting a disabled classmate to prom shouldn’t be newsworthy or remarkable. Kids with disabilities are as multifaceted as any person and deserve real, loving, deep, messy, funny, relationships. I love when kids are kind to Lamp, but even more importantly I love that she has so many wonderful friends! None of us want a world of people who simply say hi to us, but never invite us over to play, or ask us questions about ourselves, or make silly faces to each other when the teacher isn’t looking. Invite our kids to parties even when you’re not sure it’s logistically feasible, set up play dates and allow for the real ups and downs of friendship. True inclusion is true friendship.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this. And thank you even more for hopefully taking the time to have these conversations with your kids and to think about ways you can increase disability representation in your home. Please let me know if you have any questions or comments below. Once again keep in mind that I don’t have all the answers and I don’t speak for all the disability moms out there, or the disability community in general. But I have seen the positive impact of disability representation and the impact it can have! XO ~Miggy